Why “secure” is not an afterthought

Security looks scary mostly because people try to bolt it on at the end. When you start a project with the question “how to build a secure anything?”, the game changes: you think about data, attackers, and failure modes before you write your first line of code. The analytical way to approach it is simple: define what you’re protecting, map who might attack it, and then deliberately limit the damage they can do. Instead of chasing “100% safety”, you aim for layers: even if one control fails, another one blocks or at least detects the problem. That mindset matters more than any trendy framework or cloud tool you pick.

Necessary tools: not just software

Mental toolkit first

Before IDEs and scanners, you need habits: paranoia without panic, curiosity about how things can break, and discipline to actually fix what you find instead of just muting warnings.

Technical stack and helpers

On the practical side, your toolkit centers around a few core categories. You’ll want threat‑modeling notes or diagrams (whiteboard, Miro, whatever) to outline assets, entry points, and potential attackers. Then you need a version control system like Git with protected branches and mandatory reviews; this is where many beginners slip by committing secrets or merging without oversight. Linters and dependency scanners (ESLint, Bandit, Trivy, etc.) catch risky patterns and vulnerable libraries early. For people asking how to build a secure website or API, HTTPS certificates (Let’s Encrypt is fine), a hardened web server (nginx, Caddy) and a password manager for secrets are non‑negotiable. Finally, logging and monitoring tools—whether that’s a simple ELK stack or a managed service—let you see what’s really happening rather than guessing.

Step‑by‑step process

Start with a threat model, not code

Even for a tiny side project, spend an hour listing what you store, who uses it, who might abuse it, and what happens if each thing leaks, is modified, or disappears.

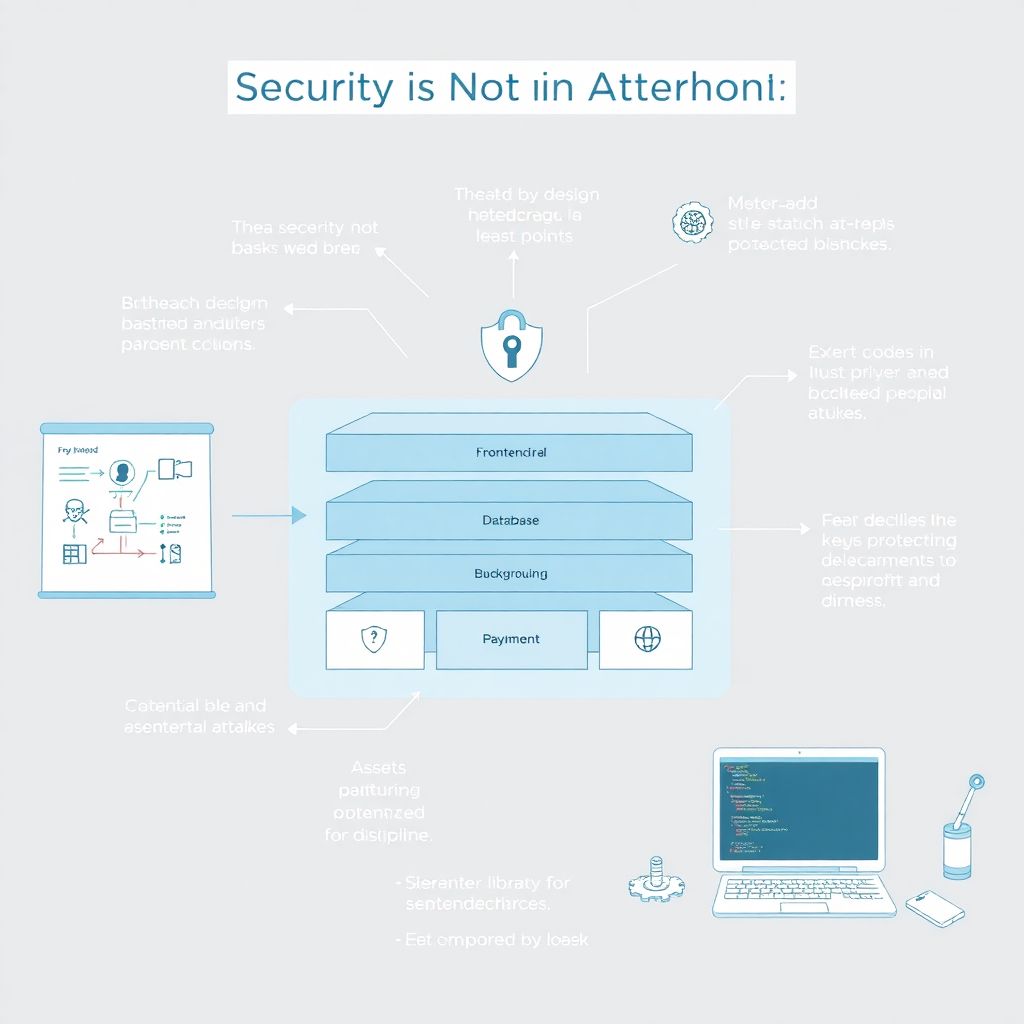

Architecture: shape risk before it hardens

Design is where you quietly win or lose. Separate components by responsibility: front end, backend, database, background workers. Give each minimum access rather than “one service that does everything with god‑mode rights”. Put public‑facing parts behind a reverse proxy or load balancer that can terminate TLS and enforce some basic rate limiting. Use environment variables or a secrets manager instead of sprinkling keys into code. When thinking about how to build a secure web application or how to build a secure ecommerce site, isolate payment flows and user data into distinct services or at least distinct schemas, so a bug in one area doesn’t instantly expose everything. The more you can compartmentalize, the cheaper every future mistake becomes.

Implementation: boring, consistent patterns

Cool tricks cause more incidents than boring standards. Pick well‑known libraries for auth, crypto, and input validation, and stick with them.

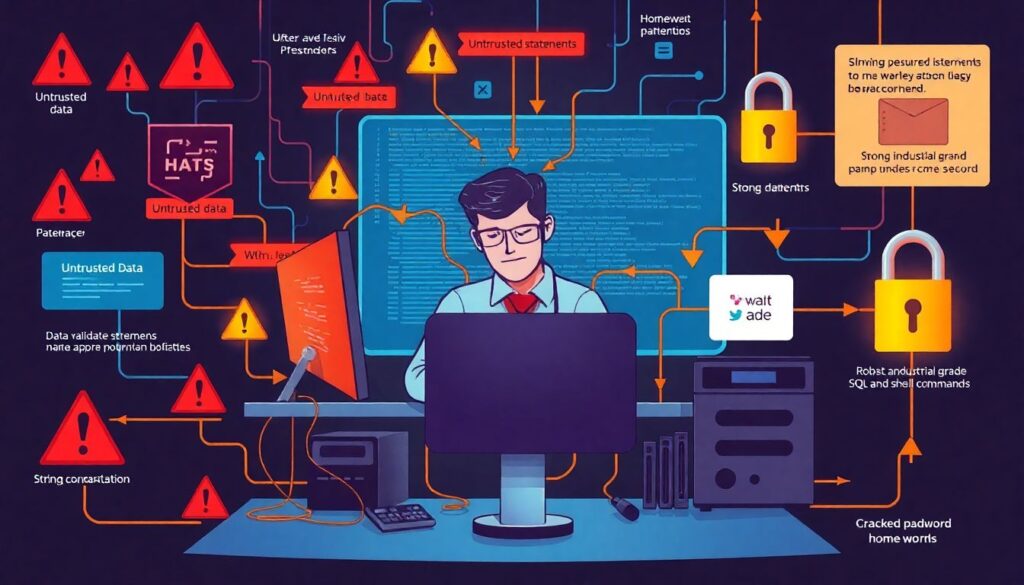

Coding with guardrails

In code, assume all input is hostile—even if it comes “from your own app”. Validate and normalize data at boundaries, use prepared statements for database access, and never build SQL or shell commands with string concatenation. For authentication, rely on proven libraries and avoid home‑grown password hashing or token logic; that’s a classic beginner trap. When someone asks how to build a secure mobile app, the honest answer starts with “stop storing secrets on the device in plain text and stop rolling your own crypto.” Use platform keystores and stick to HTTPS with proper certificate validation. For those wondering how to build a secure online platform with multiple services talking to each other, prefer short‑lived tokens, strict scopes, and explicit allow‑lists for which service may call which API. Reducing implicit trust between components is one of the highest‑leverage design decisions you can make.

Troubleshooting and common mistakes

Newbie pitfalls you really want to skip

Beginners often treat warnings as noise and logs as something they’ll “wire up later”. That’s how incidents go unnoticed for weeks. Another frequent mistake: mixing environments. Using the same database for dev and prod, or sharing admin passwords among team members, guarantees that one lost laptop becomes a large breach. Many first‑time developers also forget to rotate keys and credentials; secrets live forever, so old backups become time bombs. Overconfidence is another trap: people follow a single tutorial on how to build a secure web application and then stop questioning defaults, even though frameworks can be misconfigured in a hundred ways. Finally, documentation is underrated; if nobody knows how the security model is supposed to work, they’ll quietly route around it when it gets in the way.

Debugging security issues without panicking

When something looks off—suspicious logs, weird latency, random 500 errors—resist the urge to “just restart everything”. Freeze what you can: capture logs, preserve config snapshots, note timestamps. Then narrow the blast radius: revoke tokens, rotate critical keys, and, if necessary, temporarily restrict access to high‑risk actions. Trace the path of the suspicious request through your system to see which checks did and didn’t fire. A very common rookie move is to patch the specific bug but keep all the unsafe assumptions that produced it. Instead, ask: “What class of problems is this part of? Where else could the same pattern exist?” Whether your focus is how to build a secure website or how to build a secure mobile app backend, this habit of generalizing from incidents turns painful bugs into structural improvements.

Final thoughts: make security part of “done”

The boring but reliable way to think about how to build a secure ecommerce site or any other product is to weld security into your definition of “done”: no feature ships without basic validation, logging, access control, and dependency checks. You don’t chase perfection; you iterate. Each cycle, you harden a different layer—config today, auth flows next week, observability after that. Over time, you move from “hoping it’s fine” to being able to explain, step by step, why an attacker would have a hard time causing real damage. That clarity is the real sign you’re building something secure, not just something that feels safe.